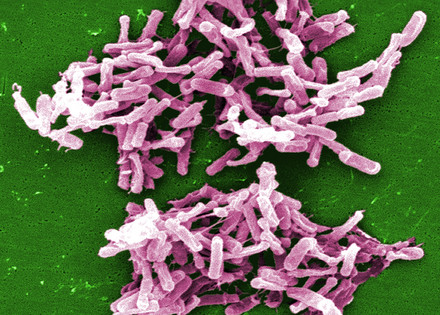

Usually, Clostridioides difficile does not enjoy a good reputation: the bacterium is considered one of the most common problem bacteria in hospitals. It can cause severe inflammation of the intestinal wall, for example, after antibiotic therapy. In a study sponsored by the DZHK, scientists have now possibly discovered a good side of the bacterium: In a severely calorie-reduced diet, it promotes weight loss but without triggering inflammation.

The scientists transferred stool samples they had collected from 80 female probands with mild to severe obesity before and after a diet to mice. The test animals had been kept germ-free and thus had no intestinal flora of their own. The team led by DZHK scientist and study author Professor Joachim Spranger of Charité Berlin made an astonishing observation: animals that received the stool collected after the diet lost weight - more than 10 percent of their body mass within just two days. The animals that received the stool taken before the diet lost no weight.

"Hungry" intestinal flora makes pounds fall off

A change in the intestinal flora, also called the microbiome, was responsible for this: The diet allowed Clostridioides difficile bacteria to multiply more quickly. The increased amount of bacteria makes it harder for the body to absorb food through the intestinal wall. A kind of "hungry" intestinal flora develops, which absorbs more sugar compounds. Toxins produced by the bacteria are also associated with weight loss. However, neither the test subjects nor the animals showed signs of intestinal inflammation.

"It is unclear so far to what extent such asymptomatic colonization with C. difficile can impair health or possibly even promote it if the bacterium does not spread too far," says Professor Spranger. The results now need to be investigated in larger studies.

The study results could lead to therapeutic approaches for diseases such as obesity or diabetes. To this end, the team is now looking into how the intestinal bacteria can be influenced so that they have a beneficial effect on body weight and metabolism in humans.

Source: Press release of the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin